The Evolution of Domestic Spying Since MLK in Memphis

Memphis began spying on local activists around the time when Martin Luther King came to advocate for city sanitation workers. A 1976 consent decree was supposed to put an end to that, but a new pending lawsuit against the city suggests it's still happening.

Last week, on April 4, the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, thousands of people poured into the streets of Memphis, where King was killed, holding signs that read “I AM A MAN,” which were the signs held in protest by striking city sanitation workers that King had aligned with in 1968. The marchers from last week were commemorating the 1968 strikes even though the city of Memphis treated the workers, at the time, in the same way that a nation treats its enemies, by spying on them.

And it’s not just the kind of spying that the FBI was already conducting on King. There was a separate level of surveillance conducted by Memphis police on social justice activists back then, and many protestors still feel subject to surveillance in Memphis today. An agreement the city signed back in the 1970s to stop clandestine tracking of activists was supposed to put an end to such practices. Instead Memphis, and other cities, seem to have just come up with more stealth ways of watching its political dissenters.

In 1965, the Memphis police department set up a domestic intelligence unit and shortly after began dispatching undercover police to “silent peace vigils” that anti-Vietnam War activists were holding at the city’s federal building. When city garbage workers began planning to organize with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees labor union in 1968, theMemphis mayor intervened by sending undercovers to collect intelligence on their activities.

Never mind that two trash collectors had just been killed by a nonfunctioning city garbage truck, or that most sanitation workers were making barely above minimum wage, or that there was nowhere for the workers to shower after long days of collecting the city’s refuse. The city saw them as a threatening force and refused to budge an inch on the union’s modest demands, even immediately after King was killed.

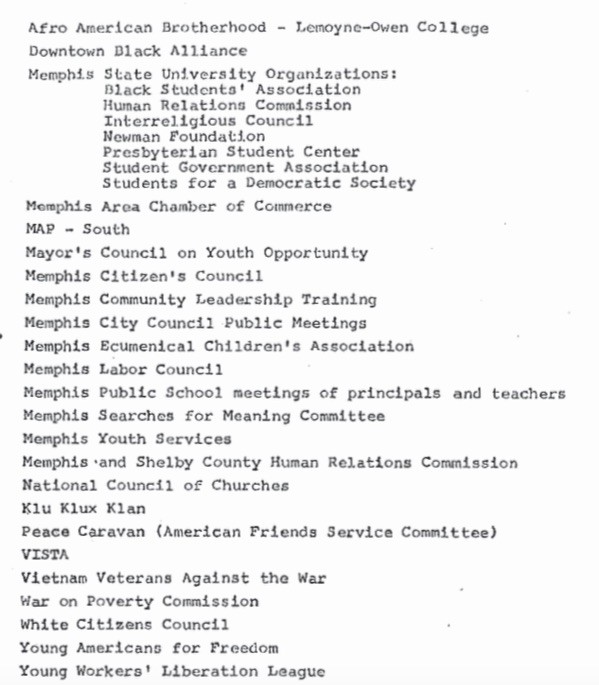

The city spying didn’t stop there. The Domestic Intelligence Unit began surveilling pretty much any organized gathering of dissenters it could get its eyes on: civil rights groups, churches, white supremacists, school teachers—few groups were apparently safe:

The city spied on these groups well into the 1970s. Despite Memphis’s previous unwillingness to raise sanitation workers’ wages to livable levels, the city was able to find $1 million for its domestic spy unit, plus an additional $10,000 for informants, in 1976. That year, Eric Carter, a University of Memphis student who also led an anti-war student organization, discovered that his roommate was an undercover cop who was collecting intelligence on their activities. The Memphis police department dismissed Carter’s requests for them to hand over their files on him when he confronted them about it.

When the ACLU of Tennessee launched an investigation in 1976 into the Memphis domestic intelligence unit, the police began destroying documents and the intel it had collected on local organizations, and continued to do so at Memphis Mayor Wyeth Chandler’s request, even as the ACLU obtained a restraining order from a federal judge demanding that it stop. According to court records, police officials “hurriedly” took nine years of photos and documents from the unit to a city incinerator where it was doused in gasoline and burned. The mayor disbanded the domestic intelligence unit the same day the restraining order came down.

The ACLU filed a lawsuit that year challenging the city for having created the secret police spying unit in the first place, arguing that it was a violation of First Amendment rights to free speech and assembly. “Defendants’ conduct chilled the exercise of said rights by instilling the fear that plaintiffs and others similarly situated will be made subjects of dossiers or reports by the Domestic Intelligence Unit or other units of the Memphis police department,” reads the complaint.

That lawsuit led to a consent decree signed in 1978 prohibiting the city of Memphis from ever again collecting “political intelligence” on any individual or organization. The consent decree was the first of its kind in the nation, and it triggered other cities such as Seattle, D.C., L.A., New York, Detroit, and Chicago to pass legislation to ban spying on its activists as well. The Memphis consent decree is still in effect and it precludes the city from engaging in any kind of electronic surveillance, employing secret informants, and from harassing or intimidating anyone who is involved in political protests.

“The City of Memphis shall not, at any lawful meeting or demonstration, for the purpose of chilling the exercise of First Amendment rights or for the purpose of maintaining a record, record the name of or photograph any person in attendance, or record the automobile license plate numbers of any person in attendance,” reads the consent decree.

However, the way that Memphis has treated its activists and residents in recent years suggests either that it forgot the terms that it agreed to forty years ago, or that the current stage of technologically enhanced surveillance and internet-tracking methods has rendered those terms obsolete. Today, dozens of police-issued “SkyCop” cameras tower over almost every neighborhood of the city, tracking the activities of the people below them.

This is perhaps not exactly what Jane Jacobs meant by “eyes on the streets,” but they purport to serve a similar, if non-organic, function of deterring crime. Since this program was authorized by the Memphis city council, it is immune from the consent decree terms, but police have found other ways to collect intel on people in less-transparent ways.

In March 2017, the ACLU of Tennessee filed a lawsuit against the city after it was discovered that authorities had created a list of names of people who would need a police escort when visiting City Hall because of their participation in Black Lives Matter and other anti-police violence demonstrations.

“If any surveillance was conducted for the purpose of gathering political intelligence, it would flout the consent decree that’s been in place for nearly four decades,” said Thomas H. Castelli, legal director of the ACLU of Tennessee in a press release (the ACLU otherwise refused comment for the story citing ongoing litigation). “Likewise, the creation of a police escort list based on people’s speech, assembly, or associations would clearly chill protected expression, in violation of the First Amendment.”

The lawsuit is still moving forward, currently in the discovery phase, with a trial lined up for August this year—which suggests that there is more to the story than just the police escort list. In fact, the ACLU’s complaint accuses the Memphis police department of “video recording participants at lawful protests” and “employ[ing] software that surveils social media posts.”

The city of Memphis refused to comment to Citylab citing ongoing litigation. However, in its answer to the ACLU’s complaint filed with the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Tennessee, it denies that the consent decree “is presently in full force and effect” today. The city admitted in the brief that one of its police “Sky Cams” captured video of a protest in front of its City Hall in February 2017 and that police body cams have recorded protests as well. But it denies “that the Police Department has acted with the purpose of gathering ‘political intelligence’ or conducting ‘political surveillance.’” The city also denies that its social media tracking software violates the consent decree terms.

Many people who flocked to Memphis last week for the “I AM A MAN” commemorative marches were probably unaware of these allegations. In fact, you could tell who was in Memphis marching as a celebratory gesture and which people were local activists who were there to actually protest, because the latter were confronted by Memphis police.

As local journalist Micaela Watts reported for MLK50.com, several activists from the Memphis-based organizations Communidades Unidas en Una Voz and the Memphis Coalition of Concerned Citizens were arrested during demonstrations against the city’s detention of immigrants and the city’s lack of high-paying jobs (Memphis is considered the poorest large metropolitan area in the nation). The activists danced and sang as part of a “Rolling Block Party,” which disrupted traffic on some of Memphis’s major roads and distribution routes were organized in part by the “Fight for $15” campaign to raise wages. Organizers from this campaign and the Mid-South Organizing Committee are also party to the lawsuit filed against the city of Memphis last year for illegal police surveillance and harassment.

After last week’s arrests, one of the organizers Naomi Van Tol, when interviewed by The Guardian suggested that the police “obviously targeted” them, saying that “they know who they’re looking for.”

This kind of targeting is far easier for police to do than it was in King’s day. Police departments now have access to equipment that can unlock and grab data from people’s cell phones, monitor social media accounts, and profile people via their license plates. These are the kinds of activities that the 1978 Memphis consent decree was intended to get rid of. A popular saying among activists goes, “They tried to bury us; they didn’t know we were seeds”—apparently the same has been true for the burial tools.

Comments

Post a Comment