The Wild Comeback Of New York's Legendary Landfill

At Freshkills Park, where the city dumped 150 million tons of its garbage, human desires and nature’s needs are feeling their way to a new harmony.

This post is part of a CityLab series on wastelands, and what we squander, discard, and fritter away.

Twenty minutes past the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to Staten Island, the smell would hit. Cait Field, who grew up nearby on Long Island, remembers this from childhood car trips—how her parents would roll up the windows and flip the AC’s recirculate button while acres upon acres of fetid household garbage scrolled past. The scent alone signaled that the Fresh Kills landfill was where things went to rot, not live—except for thousands of feasting seagulls.

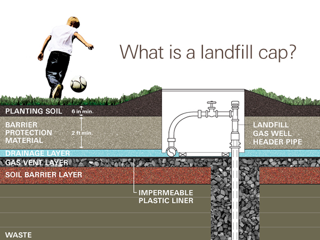

But the Fresh Kills of memory has remarkably little to do with its present. On a blue-skied and frigid Valentine’s Day, Field, now a 33-year-old scientist, stands atop one of those gigantic trash mounds. You can see the Manhattan skyline in the distance, but not one scrap of garbage. The flocks of feasting gulls have moved on, though Field does spot a lone soaring hawk. Beneath her feet lie some 150 million tons of New York City waste, immobilized, covered, and capped with tiers of thick soil, impermeable plastic, and gas-containment pipes. On the top of this layer cake grow native grasses, mowed short for winter. The only smell is moisture in the breeze whistling against her brown puff jacket.

“This is the area the grasshopper sparrows really like,” Field says, nudging the dried fibers with her boot. On another mound, she’d shown me how the ground cover was much thicker, having been planted years before this one. “Notice how here, it’s a much thinner carpet—we’re trying to figure out how to keep it like that,” she says.

Turning back to her Parks Department Prius, she notices a set of tracks in a patch of hardened snow. What she had taken to be a colleague’s footprints from the road are, closer up, clearly the work of geese.

What was once the world’s largest landfill is slowly transforming into a new flagship park for New York City. At 2,200 acres, Freshkills Park (its namesake creek has been rebranded as one word) will be nearly three times the size of Central Park when it fully opens in 2036. But already the soft, hilly topography—its every rise formed by garbage—is home to hundreds of species of plants and animals.

As the research program manager at Freshkills, Field’s job is to make sure the new residents are settling in, and staying for the long haul. She conducts her own research on the park’s fish populations, coordinates a rotating cast of visiting scientists, and helps develop a wildlife management plan. It’s an unusual job, to say the least. As an utterly novel, human-engineered grasslands environment—in a borough of NYC—Freshkills is in some ways a scientist’s dream. Every shift in the ecosystem can be tracked from a baseline, the point at which the garbage mounds were first capped and planted. Every uptick or dip in species population or health can be readily correlated to those trackable changes.

Where those changes are headed, though, no one really knows. Freshkills is not a story of environmental “restoration”—fifty-plus years of landfilling means that this earth will never return to what it once was. But with gentle shepherding, and not too much interference, Field and her team hope that Freshkills will live again as a newly thriving ecosystem. It may also be model for other places—perhaps even the planet itself—that have been irrevocably changed by human behavior, but can still make room for life in what was once wasted space.

“It’s hard to know the worse of two evils”

“This all would have been built on, if it hadn’t been a landfill,” says Field, as her Prius rattles down a gravel-lined switchback running alongside Freshkills’ main creek. “It’s hard to know what would have been the worse of two evils.”

That’s one of the many tensions between nature and artifice that lie at the heart of the Freshkills story. Named by 17th-century Dutch settlers for the “fresh waters” they admired here, Freshkills sprawls along the banks of an estuary on the west side of Staten Island. Once it was tidal creeks and coastal marshland, home to wading birds, blue crabs, terrapins, and diverse flowering herbs. These ecosystems filtered bits of waste in the water and functioned as absorbent flood barriers—essential in hurricane season. (What wetlands remain at Freshkills absorbed a heroic amount of storm surge during Hurricane Sandy.)

capping process. (New York City Parks Department)

Staten Island’s squishy swamps appeared valueless, however, to 20thcentury city planners. Under the all-powerful “master builder” Robert Moses (who else?), New York City turned the wetland expanse into a landfill in 1948.

The dumping was only supposed to last three years, long enough to form the foundation of a new, mixed-use residential development. But the needs of the growing city trashed those plans. In the face of ardent opposition from Staten Islanders, Fresh Kills stayed open and became the largest landfill in the world by the mid-1950s, receiving nearly 30,000 tons of garbage every day from all five boroughs at its peak. The historic tidal wetland ecosystem was utterly buried by plastic packaging, food waste, leaky electronics, and every bit of municipal detritus under the sun.

Finally, in 1996, environmental concerns and local politics pushed Mayor Rudy Giuliani and New York Governor George Pataki to sign a state mandate closing the site. The intensive process of permanently capping the mounds began. Three out of four are now completely finished, at a cost of $600 million. The city’s trash, meanwhile, gets shipped to landfills in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and beyond.

Park officials insist the process fully contains all the harmful byproducts of the waste, and that the site is safe for humans, mammals, birds and fish, as regulated by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation; the hard clay at the bottom of the site, they say, does an unusually good job of preventing leachate from seeping into waterways. The last shipment of garbage came in 2001: one million tons of debris from the fallen World Trade Center towers.

“My community visioning sessions are with the sparrows”

By the time Freshkills closed its gates to waste, the Great Man-era of city planning was dead and buried, too. Public attitudes towards landfills’ environmental impacts had shifted decisively. James Corner Field Operations, the landscape architecture firm known for its work on the High Line and other “adaptive reuse” park projects, won a city-sponsored design competition to turn Freshkills into a flourishing outdoor public space.

Rather than flatten the land into something more manicured and legibly “park”-like, the firm’s vision is to work with what’s there. Miles of multi-use trails, picnic grounds, performance stages, kayak docks, and ball courts will be built into spaces allowed by the trash-formed meadows. “You start with nothing, and you grow, through management, a more diverse ecology,” James Corner, the firm’s founding architect, told New York magazine in 2008: an anti-Moses design philosophy, if there ever was one.

Field and Freshkills’ planners are taking an analogous approach to the park’s wildlife. “We don’t know what will happen, as far as wildlife returning and what will come, because we don’t have a time-point we’re trying to ‘restore’ to,” says Field. Unlike projects that trying to turn back the clock on human destruction—a heavily logged forest in Oregon, say, or a tourist-trampled island in Hawaii—only small sections of Freshkills that were never landfilled can ever be “restored” to the tidal wetlands that once thrived there. Most of the park, on the other hand, has to be gently nudged into serving as something else entirely: an open grassland habitat, a natural setting that’s critically endangered around the U.S. The grasses have so far welcomed a diversity of raptors, sparrows, owls, rodents, bats, butterflies and a host of other local species.

With a background in animal behavior (her Ph.D work involved communication between fishes), Field thinks carefully about how the park can learn from the animals flocking to Freshkills, and what they’re “saying” as the park’s sections and amenities slowly emerge, drop by funding drop. (The full park cost is almost impossible to estimate, given how entangled it is the mandated process of landfill capping.) While her colleagues in the city solicit residents of surrounding neighborhoods for input on amenities and design, “my community visioning sessions are with the grasshopper sparrows,” she jokes.

There’s an advantage to working with them, rather than humans: “The birds don’t know it’s a landfill underneath here,” Field says. “They don’t care. There’s no perception issue for them.”

The grasshopper sparrows are indeed helping the park make key decisions. Dick Veit, a veteran ornithologist at the College of Staten Island who’s been studying birds at Freshkills since the 1990s, was stunned to find 40 pairs of the small ground-nesting birds—which are listed as a species of special concern by New York State—huddled mostly in the East Mound in 2015. “It was just exceptional,” he says. “Usually if they colonize a new area it’s one pair at a time. But we went from zero to 40 pairs in one year.”

There were far fewer sparrows in 2016, though. Veit isn’t sure why that is, or why the birds preferred the more recently capped East Mound to the others. These are the sorts of question that he and Field are trying to work out, and they may test different grasses to understand.

The same applies for animals living in the streams, creeks, and ponds that course through the park. Seth Wollney, of the College of Staten Island, and Eugenia Naro-Maciel, of New York University*, have long studied turtle populations in freshwater habitats all over Staten Island, and have found that the size and health of the turtle species and microorganisms that colonized Freshkills’ ponds—which were built as rainwater basins to catch run-off from the garbage mounds—are virtually the same as in natural ponds on Staten Island. “It’s a great argument for passive restoration,” says Wollney. What’s artificial has become, more or less, “natural.”

“We have this whole new ecosystem. Let’s see what happens”

The trick for Field and the posse of scientists working on site is to keep what’s working working, and to keep a close watch on what might be lacking. If fewer hawks appear one year, it might call for an extra delivery of small mammal prey to the park. If the turtles fail to reproduce, their breeding habitat might need adjusting. These questions will require years of longitudinal study, with careful monitoring of conditions. But the advantage of being in an environment like Freshkills is that, even if they don’t know exactly “where” they’re headed, scientists know exactly what conditions they started from.

It’s nature, after all, that’s supposed to be guiding the park along—at least for now. Veit, Wollney, and other ecologists have concerns about how viable Freshkills will remain as wildlife habitat once construction on more park amenities gets underway, and once humans begin to use them. The massive project’s progress is slow: Sixteen years after the design competition was announced, the only sections that available to the public are a few ballfields and a greenway on its the outer edges; it’ll be years before the first interior area opens its gates.

But plans to build a publicly accessible road system through the park have Veit worried that the minimum area to truly support bird populations—about 100 continuous acres—will be compromised. And he’s seen renderings with shade trees planted right at the perimeter of the grassy mounds, which look great for people, but could harm grassland conservation efforts. “The parks people keep saying there’s no way we’ll have the money to do all of these things, so that’s working on the side of conservation,” says Veit. “But some of the draft plans have a lot of stuff going on in them.”

Wollney, meanwhile, is concerned about the impact of boating on some of the tidal creek habitats, and—wait for it—people throwing trash in the ponds.

The redemption of Freshkills may never be complete, at least not from the perspective of the wildlife it’s carefully trying to court (and certainly, not as long as New York City is still exporting its garbage to landfills in other states). It’s not nearly as stark as it was during the Moses era of destruction, but the tension between human desires and nature’s needs will always be at the heart of Freshkills. And perhaps that’s fitting, since, at this point, people clearly deserve consideration, too.

“Whole neighborhoods suffered here for 50 years. How do you reconcile that?” says Tatiana Choulika, the principal designer of the Freshkills project for James Corner Field Operations. “Whatever ecologists’ concerns are, this space is never going to be closed to the public. That’s not the point of a big city park like this.”

Comments

Post a Comment