A new tool called OpenOversight matches names and badge numbers with photos of police. But some fear it could put officers’ lives in danger.

Last week, the ACLU of California released emails showing that Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram provided Geofeedia, a social media monitoring company used by several law enforcement agencies nationwide, specialized access to feeds of bulk public data. Geofeedia used the feeds to spy on Black Lives Matter activists in Ferguson and Baltimore, the ACLU also revealed. Companies like Twitter stipulate that data should not be used to “investigate, track or surveil” users, and Twitter and Facebook both moved to restrictGeofeedia’s bulk access to user data.

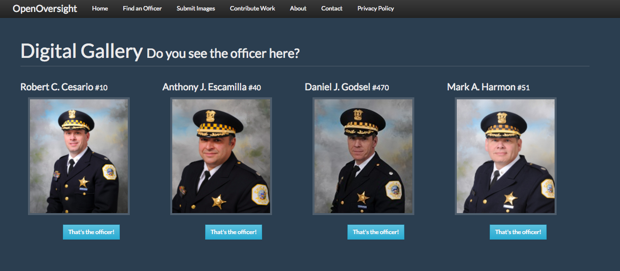

But the controversy inspired one group of digital activists to turn the tables on law enforcement. Lucy Parsons Labs, a Chicago collective of web developers—their name and inspiration comes from the Wobbly-era labor organizer who Chicago police once called “more dangerous than a thousand rioters”—has released a new tool that allows the public to collect and share social media data on police officers. The web tool, OpenOversight, is aimed at the Chicago Police Department, one of many agencies across the country that uses Geofeedia to monitor public events.

The tool seeks to match the names and badge numbers of officers (obtained by records requests) with photos (drawn from social media) to help people file misconduct complaints.

But the controversy inspired one group of digital activists to turn the tables on law enforcement. Lucy Parsons Labs, a Chicago collective of web developers—their name and inspiration comes from the Wobbly-era labor organizer who Chicago police once called “more dangerous than a thousand rioters”—has released a new tool that allows the public to collect and share social media data on police officers. The web tool, OpenOversight, is aimed at the Chicago Police Department, one of many agencies across the country that uses Geofeedia to monitor public events.

The tool seeks to match the names and badge numbers of officers (obtained by records requests) with photos (drawn from social media) to help people file misconduct complaints.

So far, the app’s gallery of officer photos draws on publicly available data from Chicago Police Department social media accounts and Flickr. Lucy Parsons Labs estimates that they currently have photos of about 1 percent of Chicago Police Department officers. According to Jennifer Helsby, lead developer of the project, the site’s identification capacity will become more robust as members of the public upload photos of officers into the gallery. The team is hoping to eventually spread the tool to cities across the country.

“The initial idea for the project came from looking at how police do social media monitoring,” says Helsby. “We talked to people who had been victims of [police] abuse and had gone to file complaint, but were told, ‘If you don’t know the badge number and name, nothing is going to happen.’”

Chicago police representatives, however, have raised concerns that OpenOversight could endanger police officers’ lives. “You put someone’s name out there, then now he’s driving with his kids or to his school, and now you’ve got him more easily identified and you put him and his family at risk,” says Dean Angelo, president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police union. ”People are doing this haphazardly, without any concern about an officer’s assignment, whether they’re working in a sensitive unit, narcotics, gangs, or undercover. They just don’t seem to care, ‘The public needs to know’—that’s the big banner that everyone is carrying. [But this] transparency [comes] at the risk of the lives of the women and men that perform this dangerous job.”

Chicago Police Department spokesperson Anthony Guglielmi did not respond to CityLab’s questions, but two former cops who are now police-reform advocates did weigh in on OpenOversight. “This is not a simple black-and-white issue, as far as I can tell,” says Norm Stamper, the former chief of the Seattle Police Department and author of Breaking Rank: A Top Cop's Expose of the Dark Side of American Policing. “I totally get why police are concerned over such an initiative. Anything that would allow somebody to exact revenge, it’s going to be resisted. I would draw a line at releasing an officers personal data—address, phone numbers, license plates. It is really important for police to understand that the work they do is, in fact, very public. So I come down on the side of disclosure.”

So does Michael A. Wood Jr., a former Baltimore police officer and a prominent proponent of civilian-led policing. “An officer’s information is already public record, and in the Facebook digital era, you can find anybody if you want to that bad,” he says. “Let everybody have the pictures. You are a public servant. That’s your job. You are to be identified to the public. You are accountable to them.”

Karen Sheley, the director of the ACLU Illinois’s police-practices project, argues that OpenOversight needs to be understood in the context of the Chicago Police Department’s failure to provide updated images of officers when complainants go to their district stations to file a complaint. “We’ve been asking for photos that you can access for years,” she says. “Not necessarily on the web, but somewhere—so that if someone has an event happen, they can go in, make a complaint, and the investigator could show them who it might be. Sometimes there are 10- year-old to 15-year-old images of officers, so when you bring in someone to file a complaint, the images are too old to identify.”

But police union spokesman Angelo disagrees. “I don’t find a lot of support for the process being either difficult to access or difficult to file a complaint,” he says. “I think it’s wide open the way it is.”

Police accountability has become a major concern in Chicago recently, as a wave of scandals and investigations has hit the department. Last year, reports emerged that police operated a secret interrogation site and allegedly fabricated details about the officer-involved shooting of Laquan McDonald. Over March 2011 to September 2015, less than 2 percent of the 28,567 complaints filed against the Chicago Police Department resulted in the discipline of officers, according to numbers assembled by the Citizen Police Data Project. That project is under The Invisible Institute, an investigative journalism nonprofit, and the Mandel Legal Aid Clinic of the University of Chicago Law School.

Public data collected by the CPD suggests that lack of information may be allowing potentially abusive officers to remain on the force.Over March 2011 to March 2015, nearly a third of officer complaints were immediately dropped in Chicago due to a lack of officer identification.

Public data collected by the CPD suggests that lack of information may be allowing potentially abusive officers to remain on the force.Over March 2011 to March 2015, nearly a third of officer complaints were immediately dropped in Chicago due to a lack of officer identification.

Helsby and the Lucy Parsons team hope that OpenOversight will help close that information gap. And she insists that it won’t endanger officers on sensitive undercover assignments, or expose others to risk of reprisal. The web gallery collects only photos of uniformed officers, she says. Its purpose is simply to help even out the power imbalance between civilian and police surveillance.

“When the police do [social media surveillance], it’s on private citizens,” she says. “When we do it, it’s on public officials walking around neighborhoods with guns.”

Comments

Post a Comment