Hartford Trains Its Hopes for Renewal on Commuter Rail

Connecticut’s new Hartford Line isn’t just a train: It’s supposed to be an engine for the capital city’s post-industrial transformation.

On a recent Thursday morning, Emily Keeney, a 30-year-old digital marketer from Queens, N.Y., was aboard a train rolling through New Haven, riding to her family home in Somers, Connecticut, for her younger sister’s high-school graduation. In the same car, Omar Eton, a 60-year-old Hartford cancer specialist, was returning to his office after appearing on a local TV news show in New Haven. Also a passenger was Nate Evans, a 27-year-old dance teacher, who lives about 40 minutes from his job in Hartford.

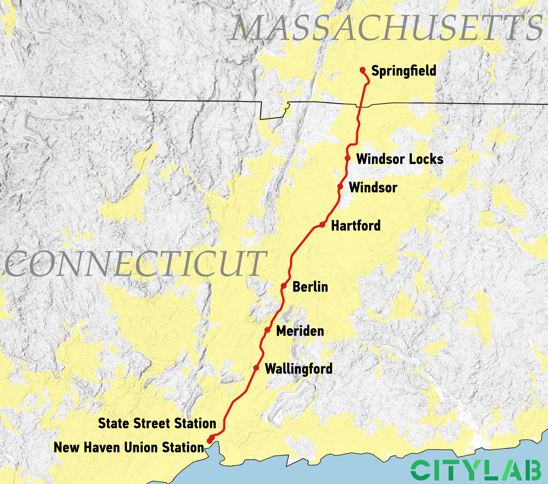

Together, they were among the first riders on the Hartford Line, the first commuter rail service to operate trains throughout the day through the cities of central Connecticut since the defunct New Haven Railroad stopped running in 1968. The new service, which launched on June 18, runs from Springfield, Massachusetts, to New Haven, making eight stops along the 62-mile Interstate 91 corridor. The full run takes about an hour and 20 minutes, with the Hartford-to-New-Haven stretch coming in around 40 minutes. During weekday rush hours, trains leave about every 30 minutes.

It’s no high-tech bullet train, but boosters in Connecticut’s struggling capital hope that the Line can be the little engine that transforms the city, spurring transit-oriented development downtown and luring youthful new residents. And it’s only one part of a whole suite of infrastructural efforts aimed at bringing life to a city overdue for renewal.

Hartford’s economic woes goes way back: Deindustrialization eroded the city’s factory base during the 20th century; riots in the late 1960s sped the flight of white residents and the middle class. By 1997, when the city’s lone big-league franchise, the Hartford Whalers of the National Hockey League, decamped for North Carolina, gloom had settled over the region’s communal psyche. In 2017, the insurance giant Aetna vowed to flee as well (then reverseditself), and Hartford famously flirted with bankruptcy. A last-minute state bailout saved the day, but lawmakers failed to address what city officials say are fundamental flaws in a municipal tax structure that makes it all but impossible to achieve fiscal stability. Hartford’s poverty rate of 31.2 percent is four times the rate of the surrounding suburbs.

Commuter rail has long been mulled as a possible solution. Its roots date back nearly 25 years, when Connecticut’s Department of Transportation undertook a feasibility study on renewing passenger service through the Connecticut River Valley. Leading the push for more trains was the Capitol Region Council of Governments, or CRCOG (pronounced “Crog” by locals), a metropolitan planning organization for the 1 million residents of 38 towns and cities across the 800-square-mile Hartford area. The group argued that commuter rail would improve the critical connection to New Haven and reduce traffic on often-congested Interstate 91. Others advocates and studies claimed it would make the region and state’s business climate more competitive by strengthening the link to New York City and other booming Northeast metros.

Comments

Post a Comment